What is Tonalism?

The following essay is reprinted courtesy of David Adams Cleveland, author of A History of American Tonalism, foremost authority on the tonalist movement in America. Reprinted with the author’s permission.

THE TWELVE CHARACTERISTICS OF TONALISM:

David Adams Cleveland

Charles Warren Eaton, Sunset Pines, ca. 1910, Private Collection, NY

The stylistic characteristics of Tonalism comprise twelve visual components or visual emotions:

1) Use of subtle color tones comprised of various greens, purples, blues, and grays that are restful and easy on the eye;

2) Aesthetic Tonalism and Expressive Tonalism;

3) Stress on Symbolic Form;

4) The depiction of atmosphere (the unseen air);

5) A sense of movement or metamorphosis in nature (the vibration and refraction of tones);

6) The use of expressive paint handling to embody emotion or mimic the felt-life of nature;

7) The employment of formal strategies of embedded patterns and the decorative deployment of natural and abstract forms (derived from Whistler and influenced by Asian art), often used in conjunction with serial renderings of the same subject in different lights and from various angles of perception;

8) The use of soft-edged forms to further the sense of ambiguity and mystery of place (known as lost-edge technique in the nineteenth century);

9) An emphasis on the broad, graphic, ultimately abstract reading of major forms, producing an immediacy of emotional response to paintings, especially at a distance;

10) A predisposition for the elegiac poetry of landscape (reflecting the trauma of the Civil War);

11) The portrayal of a mystical organic relationship between perceiver and the perceived (the transcendentalist subjectivity espoused by Emerson and Thoreau);

12) A non-narrative synthetic art: an art about the feeling or mood evoked by the arrangement of landscape elements to project an emotion, rather than a realistic or representational depiction of a certain place.

George Inness, Shawangunk Hills, 1885, Private Collection, NY

These twelve characteristics of American Tonalism rarely if ever operated in isolation from one another, rather the opposite: in most cases, several or even all the characteristics can be seen to function seamlessly in a single work, whereby the emotional emphasis of the painting is tempered by the artistic choices among and balance between these various technical/stylistic options. What’s more, there is clearly overlap and blurring of affinities, just as in any work of art employing a range of colors that blend and bleed one into the other. Nevertheless, it is useful to try and tease out these various technical and stylistic strains because it adds to our understanding of how artistic choices shaped the Tonalist aesthetic and, most especially, the progressive nature of Tonalism and the deep cultural roots out of which the movement developed. Lastly, by systematically enumerating these characteristics, the synergy between them is grasped more concretely, a synergy that is further galvanized by the qualitative and cumulative technical choices made by individual artists, each with their unique strengths and proclivities. I might further suggest that a familiarity with these twelve characteristics, almost all without exception fundamental to the modernist canon, will go a long way to educating young people about the historical blood lines of contemporary art, especially contemporary Tonalism, and so better connect them into the deeper heritage of art history. Such an appreciation and understanding and—dare I say it, level of connoisseurship is sorely lacking among today’s collectors, who, in many cases, have become overly dependent on digital images of artwork—quickly summoned and just as quickly dismissed—rather than long sessions of sweet, silent thought given over to contemplating actual artworks, and so fathoming their infinite complexity and the hard-won skills and singular visions of their creators.

Leonard Ochtman, A Silent Morning, 1909, Private Collection, NY

1) Use of subtle color tones comprised of various greens, purples, blues, and grays that are harmonious, tranquil, restful, quiet, and easy on the eye: The most obvious artistic strategy of the Tonalists, as the name implies, was the use of a subtle range of similar color tones on the scale between red and blue and yellow to produce a sensation that is quiet, cool, and conducive to reverie. These restricted earth and sky tones, with admixtures of grays and blacks, sometimes verging on monochrome, have the salutatory effect, like black and white photography, of highlighting or dramatizing the basic components of the composition, and so emphasizing the abstract and symbolic quality of natural forms. J. Francis Murphy’s Summertime, 1885, is a classic early example from this master Tonalist; the key elements of the landscape have been synthetically arranged to please the eye, while the prominent array of green tones in the meadow grass, wild flowers, and trees create a sense of bucolic repose. As a whole, the multitude of greens give the painting an ineffable sense of seasonal glory. A later work by Murphy, Summer, 1906, shows how a similar array of greens and ochers can be applied in broader swaths of energized pigment to create the same poetic effect, in which the variety and intensity of the color tones carry the emotional weight of the painting.

J. Francis Murphy, Summertime, 1885, Private Collection, NY

J. Francis Murphy, Summer, 1906, Private Collection, NY

Leonard Ochtman, Greenwich, 1896, Private Collection, NY

Similarly, Leonard Ochtman’s, Greenwich, 1896 is a lush study in the application of various green tonalities, particularly how those greens are applied in brush marks of different intensity and direction: delicate grids of spring hues broken only by the sweep of the dappled road, stone walls, and geometric forms of red-orange in the buildings.

Leonard Ochtman, Fall Meadow, ca. 1910, Private Collection, NY

While a later work, Fall Meadow, c 1910 similarly takes delight in the vigorous patterning of horizontal and vertical brushstrokes of a restricted range of umber brown tones, with the gray foreground tree anchoring the eye and relieving the surrounding hues of a surfeit of monotonous color: This predominance of rich autumnal tones gives the painting its essential emotional impact.

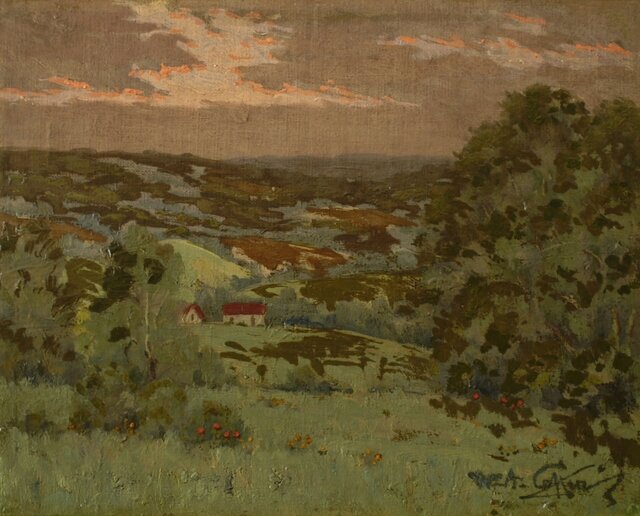

William Anderson Coffin, Sunset, Somerset County, Pennsylvania, 1924, Private Collection, NY

William Coffin’s, Sunset, Somerset County, Pennsylvania, 1924 achieves a like-minded effect with great freedom and panache, the lush layering of olive and pea greens galvanizing a visceral intensity that belies the small scale of the work.

Charles Melville Dewey, Long Island Sunset, ca.1910, Private Collection, NY

In a more traditional rendering, Charles Melville Dewey’s, Long Island Sunset of c 1910 exemplifies the artist’s use of lush earth tones to entrance the gazer with day’s fading glory.

A period review by Charles de Kay in the New York Times of an exhibition of paintings by William Sartain, see Nonquit, c. 1900, illustrates how period reviewers were conversant with the emotional quality of Tonalist color: “[Sartain’s] way of looking at the landscape is austere. He’s a very Quaker in tones and loves the broad smooth browns, the grays, the drab-colored sketches of moorlands, the pale-yellowish-brown sweeps of the sand dunes by the sea . . . a general harmoniousness as to tone.” (NYT, Thu, Feb 2, 1905, p. 9)

Paul Balmer, Green Hills, 2013, Private Collection, NY

In a contemporary vein, Paul Balmer’s, Green Hills, achieves much the same spell with a limited range of green tones, while his spirited brushwork and dramatic hatched patterns only enhance the feeling for joyous spring color.

Wolf Kahn, May Tree Line, 1993, Private Collection, NY

Wolf Kahn’s May Tree Line, 1993 brilliantly deploys a range of subtle green tones to produce a work of quiet horizontal abstraction, compelling both as a work of postmodern Tonalism and symbol of nature’s rapturous spring awakening.

2) Aesthetic Tonalism and Expressive Tonalism: As has been demonstrated in the first edition of A History of American Tonalism, the Tonalists movement evolved from an early style, circa 1880, of small scale landscapes, Aesthetic Tonalism, characterized by formal design and paint handling that is refined and nuanced, quiet and intimate in visual effect; to a later style of Expressive Tonalism, circa 1900, where the use of expressive brushstrokes on larger and larger canvases become commonplace, as modernist tendencies to display freewheeling paint handling took root in America, if not throughout the international art world. Aesthetic Tonalism with its emphasis on balanced design, subtle patterning, and a kind of otherworldly equipoise came directly out of the Aesthetic movement and artistic philosophy of art for art’s sake promoted by its greatest exponent, James McNeil Whistler, whose small scale exquisitely executed non-narrative etchings, pastels, and oils, embodied this artistic credo. By 1880, Whistler was all the rage in American progressive art circles. Whistler’s followers embraced Asian art, especially Japanese woodblock prints with their emphasis on flat formal design, repeating decorative patterns, and low-toned abstraction of organic shapes. William Anderson Coffin’s, Sunset Trees, c. 1890 is a classic example of this intimate, low-toned, and exquisite landscape mode of the 1880s and 90s; the subdued light of dusk exaggerates the barebones forms of the landscape, an artificial pattern that has been deliberately arranged by Coffin to allow the eye to wander in zig-zags from the foreground throughout the landscape, and even into the cloud-streaked sky, where the diagonal grids are echoed ad infinitum. Balance, equipoise, and sensuous form make the work an eye-catching window into some super-sensible world.

William Anderson Coffin, Sunset Tones, ca. 1890, Private Collection, NY

Franklin De Haven, Lakeside, 1885, Private Collection, NY

Lakeside, 1885, by Franklin De Haven displays a similarly mapped out synthetic design of lazy diagonals and lush natural forms, sharply delineated in the rocky shore of the foreground, receding to more hazy tree-intervals in the background—all to the end of projecting the intimacy invoked by a place of repose and reflection.

An early oil by William Gedney Bunce, Venice, Sail Reflections, 1885, demonstrates how Aesthetic Tonalism could be translated as well to marine subject matter, here mostly executed with the slashing strokes of the palette knife but retaining all the equipoise and formal design of the style. A later work by Bunce from around 1900, Venezia, shows how the latent expressionism of Bunce’s style developed into a full-blown work of Expressive Tonalism, where the pinwheels of slathered yellows—Bunce’s favorite color—careen across the dun sky of the support in an uninhibited celebration of light and color. The design element of Aesthetic Tonalism remains but the emphasis is now on the energy and reflected glory of the sunset, if not the artist’s sheer joy in creation.

William Gedney Bunce, Venice Sail Reflections, 1885, Private Collection, NY

William Gedney Bunce, Venezia, ca. 1900, Private Collection, NY

The transition from early to late style Tonalism, from Aesthetic Tonalism to Expressive Tonalism, can be illustrated in the work of scores of the best artists of the period from 1880 to 1920, none more brilliantly than that of J. Francis Murphy in his Summertime, 1885 and Summer, 1906, a twenty year stretch that illustrates how the artist’s work evolved from a masterful example of classic Aesthetic Tonalism, where every detail in the painting from paint marks to landscape forms have been orchestrated to create an aura of poetic repose and harmony, to the later landscape, where detail has been dramatically reduced, form minimized, so enabling the expressive power of the supersaturated green tones to create a kind of muted energy field that seems to radiate heat, if not the dazzle and cicada-buzz of high summer.

J. Francis Murphy, Summertime, 1885, Private Collection, NY

J. Francis Murphy, Summer, 1906, Private Collection, NY

Charles Warren Eaton, Later Winter Pasture, 1900. Private Collection, NY

Charles Warren Eaton, Autumn Meadow, 1888, Private Collection, NY

Franklin De Haven, De Haven, Orange Trees, ca. 1910, Private Collection, NY

Franklin De Haven’s, Orange Trees, c. 1910 demonstrates this artist’s later preoccupation with expressive paint handling and the channeling of nature’s energies in the gestural mark of the artist’s hand.

While Leonard Ochtman’s, Greenwich, 1896 and Fall Meadow, c. 1910, or a much larger canvas, Spirit of Fall, c. 1910, illustrates the evolution among leading Tonalists from their early emphasis on a perfectly composed conceptual art to a later energized version with its embrace of personal expression on larger supports, and ultimately, a portrayal of the carrying power of nature’s metamorphic energy as embodied in the paint mark itself.

Leonard Ochtman, Greenwich, 1896, Private Collection, NY

Leonard Ochtman, Fall Meadow, ca. 1910, Private Collection, NY

3) Stress on Symbolic Form: The Tonalist use of a narrow range of tones and the synthetic arrangement of landscape elements adds to the immediacy of the composition, strengthening the graphic read of organic, geologic, and manmade features, and thus the symbolic impact of natural forms, whether in stark silhouette or set against a neutral background. In Europe, Whistler almost single-handedly developed the symbolic mode in his mysterious Thames nocturnes, setting the example for Degas’ landscapes of the 1890s, and a host of later Symbolist painters that would come to include modernists like Gustav Klimt and Egon Shielle. On American shores, Verdant Hills, 1901, by Franklin De Haven, illustrates the expressive use of a limited tonal range in dramatizing his gesticulating tree trunks and the shape of a mass of tree tops receding into the background. Even the foreground path and boulders seem alive in this dynamic counterpoint of roiling green landforms against the spumey-blue of the sky.

Franklin De Haven, Verdant Hills, 1901, Private Collection, NY

Franklin De Haven, Storm Clouds, ca. 1905, Private Collection, NY

De Haven’s Storm Clouds, c. 1905 achieve a similar power in focusing the composition on billowing cloud formations that dwarf the wind-bent trees in the foreground.

Franklin De Haven, De Haven, Orange Trees, ca. 1910, Private Collection, NY

While a later work by De Haven, Orange Trees, 1910 enhances the symbolic force of the two trees—a flurry of jotted paint marks—by juxtaposing them against a sky of swirling clouds.

Charles Warren Eaton achieves a similar if more subdued effect in his brooding watercolor, Gloaming Pines, c. 1910, where the extremely limited range of earth tones enforces a stark and compelling vision of a copse of white pine in near-silhouette. An effect further heightened in Eaton’s, Forest Edge c. 1904, where the soft-edged pine boughs verge on total two-dimensional symbolic abstraction, forms imprinted upon the sunset horizon where the horizontal bands of yellow-gold hues have been transmuted into formal elements of the interlocked composition.

Charles Warren Eaton, Gloaming Pines, ca. 1910, Private Collection, NY

Charles Warren Eaton, Forest Edge, 1904, Private Collection, NY

Ben Foster, Hillside Trees, ca. 1910, Private Collection, NY

In 1904, this was still a cutting-edge strategy, fully absorbing Japanese models of woodblock prints and, in turn, fueling the Arts and Crafts Movement and its use of similar graphic imagery for decorative objects. Ben Foster’s, Hillside Trees, c. 1910 provides yet another variation on tree trunks as abstracting elements, here in cropped verticals on a sharp incline, creating an array of colored apertures from the lighted areas behind.

Charles Melville Dewey, Long Island Sunset, ca.1910, Private Collection, NY

Long Island Sunset by Charles Melville Dewey, c. 1910 depicts the lush natural symbolic forms most dear to the Tonalist imagination, here partially enumerated in a New York Times review of Dewey’s work in 1916: “The large silhouette of the tree masses, the breadth of the nobly designed sky, the solidity of the earth, are elements of that sense of security in the working of eternal laws throughout the universe which the sight of wide horizons at still moments in inspires.” (NYT, Sun, April, 16, 1916, p. 78)

In a similar manner, the Tonalists were able to convincingly portray their favored themes by the strategic arrangement of natural symbols, going beyond the standard repertoire: trees and tree trunks, boulders, hill shapes, horizon lines, stream banks, sun and moon orbs, and a plethora of cloud formations, to include the iconology of abandoned farmlands in the northeast, especially overgrown pastures and paths and roads, crumbled fences of stone and wood, along with the occasional roofline or barn or chimney releasing a ropey writhing of wood smoke into a fading sky.

Charles Melville Dewey, Sunset After Rain, ca. 1895, Private Collection, NY

William Morris Hunt, Moonlit Shore, 1864, Private Collection, NY

Frederick Kost, Hillside Boulders, ca. 1910, Private Collection, NY

Walter Nettleton, Winter Light, ca. 1900, Private Collection, NY

Wolf Kahn, River Mosaic, 1990, Private Collection, NY

4) Depiction of Atmosphere (the unseen air): The Tonalist’s use of a predominant tonality had the collateral effect of creating a pronounced atmospheric quality in which the very air that infuses the landscape has a palpable density and optical resonance.Hugh Bolton Jones’ Coastal Landscape, c. 1879, probably painted in Brittany, illustrates how many American artists working in the American artist colonies in Brittany in the 1870s developed a predilection for the silvery gray atmosphere or micro-climate of that then still-remote coastal countryside, a habit of mind and eye the expatriates brought back to American painting grounds, there settling on places with similar qualities of weather, and/or employing depictions of dawn and dusk, autumn and winter, in which the weight of the atmospheric envelop is most pronounced.

Hugh Bolton Jones, Coastal Landscape, ca. 1879,Private Collection, NY

Alexander Harrison, Olive Trees, 1909, Private Collection, NY

Olive Trees, 1909, painted in Brittany by Alexander Harrison, illustrates the artist’s mastery for creating the illusion of vibrant atmosphere in which all features of the landscape are magically transformed to project a kind of otherworldly aura, providing both pictorial unity and a supersensible charm that so bewitched the young Marcel Proust, who knew Harrison and his Tonalist landscapes, and later transformed the expatriate artist into the character Elstir in Remembrance of Things Past, while writing subjective descriptions of landscape uncannily like the sensuous renderings of Harrison.

William Anderson Coffin, Sunset Tones, ca. 1890, Private Collection, NY

Sunset Trees, c. 1890 by William Anderson Coffin displays a masterful rendition of the sultry air of a summer sunset, while graphically depicting the lineaments of this Pennsylvania landscape, which the artist has orchestrated into interlocking diagonals to channel the eye in a deliberate recessional movement. In a more traditional vein, William Gedney Bunce’s, Nocturne Venice, 1890 wonderfully renders the moonlit evening on the lagoon, the brine saturated air transformed into nacreous horizontal bands of patterned light.

William Gedney Bunce, Nocturne, Venice, ca. 1890, Private Collection, NY

Arthur Bowen Davies, Surfside, ca. 1910 Private Collection, NY

A more Whistlerian version of the all-encompassing air is found in Arthur B. Davies, Surfside, c. 1910, in which a minimalist rendering of sand, tides, and sky emerges from the monochromatic ground of the panel.

Charles Harry Eaton, Gloaming, ca. 1890, Private Collection, NY

A near hallucinogenic depiction of sunset, when the sun has already slipped far beneath the horizon, is found in Charles Harry Eaton’s, Gloaming, c. 1890: the blur of green tones and glazed water-reflected light speaks to the whispered gasp of the day’s lingering heat.

Charles Warren Eaton, Twilit Sky, ca. 1910, Private Collection, NY

Charles Warren Eaton’s, Twilit Sky, c. 1910 shows how a masterful watercolorist can capture the saturated light of evening in this medium, here employing innovative blotting techniques to impart a streaky granular quality to the fading sky: a haunting atmospheric effect that transfigures all with a spellbinding and tangible haze.

Ben Foster, Rainy Autumn Day, ca. 1914 Private Collection, NY

In Rainy Autumn Day, 1914, Ben Foster has explicitly captured the qualities of a rain-soaked fall afternoon in which the damp blurring of forms creates bewitching patterns across the landscape, describing a crisscrossing of stream banks, walls, and roads that allow the eye a languid recessional wandering until reaching the backdrop of Connecticut’s Cornwall hills and the proscenium grey of the sky.

J. Francis Murphy October Mist, 1906 Private Collection, NY

An even more dramatic and explicit rendition of weather effects is J. Francis Murphy’s October Mist of 1906, where the sumptuous veil of heavy mist creates a softly muted color-saturated field of marvelously modulated paint marks; the mist itself becomes both titular subject and the transformative essence of the scene: where paint has been transmuted into air.

New York Times critic, Charles de Kay, reviewing a William Sartain exhibit in 1905, notes, as he did in so many of his reviews, the micro-climate so skillfully invoked by Tonalist artists: “The structure of the landscape as it must have been when drawn on the canvas is softened and veiled until the effect is that of an atmosphere full of the vapor of the seashore . . . There is great poetry of a Wordsworthian reserve and simplicity in this quiet seaside view. The ocean is not visible but it is implied.” (NYT, Thu, Feb 2, 1905, p. 9) Or in a review of Charles Melville Dewey’s work: “The earth hangs in that atmosphere of peace which strikes most poignantly upon the human heart accustomed to the warring of complex emotions.” (NYT, Sun, April, 16, 1916, p. 78) Arthur Bowen Davies’ Blue Distance, c. 1926 takes the Tonalist fascination with atmosphere to its logical conclusion: where the envelop of air through which all objects are seen has become both subject and object. As so many of the period titles indicate, the precise seasonal and climatic circumstances and the subjective feelings they invoke were subjects of great moment for the Tonalists and their collectors.

Wolf Kahn Rooftops, 1973 Private Collection, NY

Arthur Bowen Davies Blue Distance, ca. 1926 Private Collection, NY

5) A sense of movement or metamorphosis in nature (the vibration and refraction of tones): In the age when Darwin’s theory of evolution was revolutionizing science and attitudes towards traditional religion and literary culture, the Tonalist artists, thoroughly steeped in Darwinism as well as transcendentalist authors Thoreau and Emerson, intently explored the hidden modalities of nature, and the inexorable process of evolution and metamorphosis operating beneath the surface of all things, a process of transformation mirrored in the very act of artistic creation itself. Atmosphere was not just a transmitter of mood but an energy field alive to the painter’s touch. Technical advances, assimilated by American artists working in Europe allowed artists to approximate the visual sensation of metamorphic light energy in nature by applying paint marks of similar tones in juxtaposition to one another, refraction, or layering brush marks over a complementary ground tone, vibration, in which cool overtones are painted freshly into warm undertones, with the undertones allowed to break through to the surface of the canvas. A technical resource superbly executed in J. Francis Murphy’s early 1885 work, Summertime, where the foreground meadow grass to the right and left of the old farm road display the use of green paint marks of varied tones, placed cheek-by-jowl, or overlaying the warm neutral ground, so that the greens have a visual jitter—vibration and refraction, an uncanny aural approximation of the hum of cicadas on a late summer day.

J. Francis Murphy, Summertime, 1885, Private Collection, NY

Charles Harold Davis Autumn, ca. 1910, Private Collection, NY

In Autumn, c. 1910, Charles Harold Davis achieves a similar effect, here using more broken and activated paint strokes that blur in the eye as the meadow is transformed under the fading seasonal light of fall.

Charles Harry Eaton Reflections, ca. 1910 Private Collection, NY

An examination of the banks of the stream in Charles Harry Eaton’s, Reflections, c. 1910, displays the wonderful effects achieved by placing a modulated array of green tones in juxtaposition to one another, describing both summer’s scintillating light and a visual feeling of pulsing movement, as if the landscape is a living-breathing organism. A sensation reinforced by the reflected greens in the water, undergoing their own fluvial permutations.

Ben Foster Golden Hill, ca. 1910, Private Collection, NY

The steep hillside in Ben Foster’s, Golden Hills, 1910 demonstrates how a similar effect can be achieved with various tones of burnt sienna, sap green, and yellow brown, so that the rising slope, empty of the charming details usually associated with such scenes, comes alive in the activated paint surface, full of suggested motion as the blurred forms of scattered bushes and small trees swim in lazy upward patterns, endowing the otherwise ordinary with a fluid inexpressible vibrant beauty.

This sense of motion created by activated light and color was often remarked upon by period critics: “[The light] winds its way among the foliage, strays across the backs of the idle sheep, strikes the reflecting surface of a pool, and plays the part of the joy-bringing god Apollo in this cosmic drama. Under its influence all the subtleties of color in the chromatic pattern fall into order and harmony as dancers move to music. The complication of the foreground flexibly unrolled to express in sensitive modulations the gradual recession of the landscape and the perfect equilibrium between the fluent mists of distance and these sharp notes of foreground interest . . . ” (NYT, Sun, April 16, 1916, p. 78, review of Charles Melville Dewey) Perhaps the most daring, subtle, and technically astute employment of this method of tonal vibration and refraction is found in J. Francis Murphy’s late works, such as Flaming Trees, 1917 in which the reds and scarlets in the foreground tree fairly pulse with compressed energy, while the broad sky behind, a craggy variegated paint surface, comprised of an array of whites, nacreous grays, and off-yellows, provides a prismatic backdrop activated as much by color juxtaposition as the scumbled, angled, and slashed paint activated by the prevailing light as it is absorbed and reflected in an infinite array of tones.

J. Francis Murphy Flaming Trees, 1917 Private Collection, NY Private Collection, NY

J. Francis Murphy, like his fellow Tonalist, Ralph Blakelock, was a master at creating such multi-faceted surface textures that both approximate the transformative face of nature while producing qualities of refraction and vibration—an atmospheric envelop that throbs with intuited life. Virtuosos of glazing techniques like George Inness and Dwight Tryon often employed multiple layers of glazes—colored pigments infused in varnish and oil—to create prismatic gemlike surfaces that emanated a kaleidoscopic array of scintillating color, responding, like the landscape itself, to various lighting conditions.

George Inness, Spirit of Autumn, 1891, Colby College Museum of Art

Ralph Albert Blakelock, Russet Fall, ca. 1895, Private Collection, NY

Dwight Tryon, Autumn Landscape, ca. 1887, Private Collection, NY

Ben Foster, Back From the Sea, ca. 1910, Private Collection, NY

Henry Snell, Cornwall Coast, ca. 1900, Private Collection, NY

Frank Duveneck, Antique Shop, 1906. Private Collection, NY

6) The use of expressive paint handling to embody emotion or mimic the felt-life of nature: What is noteworthy about the Tonalists is how early expressive paint handling came to the fore, especially among progressives like John Twachtman, J. Frank Currier, and William Gedney Bunce, who were exposed to the teaching of the Munich School, which put a premium on flashy and dexterous paint handling. J. Frank Currier’s Setting Sun, c. 1880 is far ahead of most of his contemporaries in either America or Europe in the slashing expressive freedom of his watercolor and pastel methods, creating a surface energy that both approximates nature’s underlying forces while augmenting the inherent symbolic power of landscape forms: trees, rooflines, clouds, horizons and the atmosphere that encloses them. (Only Courbet, Whistler, and Degas, especially his pastel and monotype landscapes of the 1870s, approached Currier’s exuberant freedom of expression.)

J. Frank Currier (Joseph Frank Currier), Setting Sun, ca. 1880, Private Collection, NY

Alexander Helwig Wyant, Gray Hills, 1879, Private Collection, NY

Alexander Wyant, about the same time, in his extraordinarily precocious, Gray Hills, 1879 manages to capture the brooding stormy face of nature by using only abstract paint marks to create his dramatic landscape, mirroring the intuited energies aswirl in the raw scenery depicted. It is hard to think of another artist at this date, American or European, who could render a subject with such untrammeled freedom and subjective power.

William Gedney Bunce, Venezia, ca. 1900, Private Collection, NY

William Gedney Bunce is yet another Tonalist who used a slashing style of paint handling in the early 1880s, only to further indulge his love of gestural abstraction in his late works, gaining expressive power with age until his work neared complete dissolution of form. Venezia, 1900, is a dazzling example of Bunce’s exuberant use of color in an expansive sky that is as much about the natural forces of air and atmosphere as it is an expression of the artist’s subjective or imitative identity with these powers, as if his hand and eye seek a merging with the arrayed light sources bouncing from sky to lagoon and back again.

J. Francis Murphy, Spring Mist, 1905, Private Collection, NY

Even a relatively subdued work of 1905 by J. Francis Murphy, Spring Mist, displays an exquisite use of expressive facture on a limited scale, and a telling sense of nature’s metamorphic quintessence in its quietest moments. Yellow Foliage by Ben Foster, c 1910, although more constrained in its flurry of leafy yellow brush strokes, seeks a similar approximation between the means of paint handling and the fall breeze playing across the receding tree line.

Ben Foster, Yellow Foliage, ca. 1910, Private Collection, NY

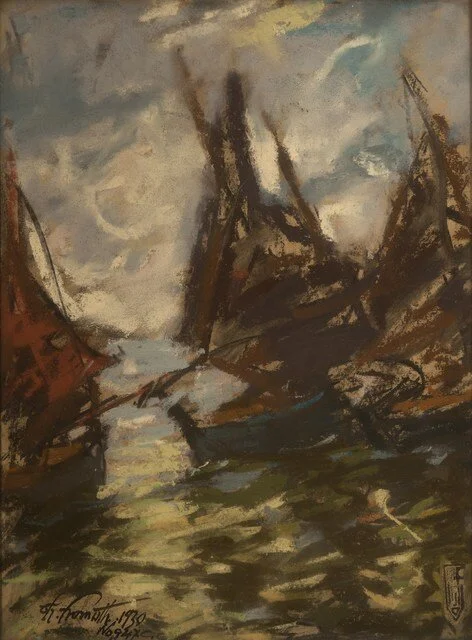

Charles Fromuth, Wind and Sea, 1930, Private Collection, NY

While Charles Fromuth’s, Wind and Sea, 1930, has moved towards near complete abandonment of form in the depiction of sea, sky, and the sardine boats plunging through the waves: all the forces of nature come together in seamless interaction.

Clifford Isaac Addams, Union Square, ca. 1928, Private Collection, NY

Clifford Addams’, Union Square, c. 1930 shows how such expressive paint handling in a Whistlerian mode is equally suited to the depiction of the hustle and bustle of an urban setting, in which the crowds hurrying along 14th street in the dusk are barely discernible as individuals, a crowd interacting as a kind of human force fields amidst urban canyons and the clutter of thoroughfares.

7) The use of formal strategies of embedded patterns and the decorative deployment of natural and abstract forms (derived from Whistler and influenced by Asian art), often in conjunction with serial renderings of the same subject in different lights and from various angles of perception: As we have seen in the previous discussion of Aesthetic and Expressive Tonalism, Whistler first became a force in American art circles in the 1880s, when the formal devices of Asian art were being adopted by the most progressive artists of the era, when Aesthetic Tonalism became the lingua franca of the earlier adopters of Tonalism as they broke with the Hudson River School. These formal characteristics remained central throughout the forty odd years when the Tonalist movement was at its height. We have already examined William Coffin’s Sunset Tones, c. 1890, as a classic example of Aesthetic Tonalism with its serene and sensuous proportions and whispered equilibrium.

William Anderson Coffin, Sunset Tones, ca. 1890, Private Collection, NY

William Gedney Bunce, Venice Sail Reflections, 1885, Private Collection, NY

Dwight Tryon, Spring Pasture, 1899, Private Collection, NY

Ben Foster, Hillside Trees, ca. 1910, Private Collection, NY

Emil Carlsen, White Pine, 1926, Private Collection, NY

Hugh Bolton Jones’ Winter Light, c. 1900 demonstrates another use of zig-zag patterning of snowy banks, complimented by skyline horizontals, while Ben Foster’s, Rainy Autumn Day, 1914 employs the same principle with a careful arrangement of landscape elements to weave his composition together as tight as a piece of dyed gingham.

Hugh Bolton Jones, Winter Light, ca. 1900 Private Collection, NY

Ben Foster, Rainy Autumn Day, ca. 1914 Private Collection, NY

Ben Foster, Back From the Sea, ca. 1910, Private Collection, NY

Foster’s, Back from the Sea, c. 1910 takes a much more complex arrangement of dune grasses and teases out an array of light and dark patterns with the intensity of unfolding fractals.

Henry Snell, Cornwall Coast, ca. 1900, Private Collection, NY

Similarly, Henry Snell’s, Cornwall Coast, c. 1900 is all about the artist’s portrayal of the interlocking color forms that compose a landscape where the intense green of cultivated pastures jostle the geologic striations of a raw cliff faces along the Cornwall coast.

Frank Duveneck, Antique Shop, 1906. Private Collection, NY

Frank Duveneck in his Antiques Shop, c. 1900, certainly inspired by Whistler’s Chelsea shop fronts, created an exquisitely designed grid of verticals and horizontals on a small scale, using rapid brushwork to sumptuous effect.

The greatest practitioners of these synthetic and formal arrangements of landscape forms were able to reassemble their elements so that the artificial patterns created echo, in an uncanny and often haunting manner, the underlying physical armature of the biosphere: measure for measure. Thus, under the artist’s intense gaze, nature reflects an underlying reality more profound than the mundane quotidian captured in a conventional snapshot view.

Arthur Bowen Davies, Nocturne in Blue and Green, 1924, Private Collection, NY

William Anderson Coffin, The Plain, Late Afternoon, ca. 1890, Private Collection, NY

Wolf Kahn. Edge of the Trees, 1993, Private Collection, NY

8) The use of soft-edged forms to further the sense of ambiguity and mystery of place (known as lost-edge technique in the nineteenth century): Given the Tonalists fondness for the transcendentalist authors, Emerson and Thoreau, and their naturalist followers like William Burroughs and John Muir, it is hardly surprising that a subjective feeling for the underlying mystery and wonder of the natural world should be all pervasive. A critical stylistic aspect of this artistic strategy is a tendency to ambiguity of form as opposed to a detailed graphic depiction, soft-edged forms as opposed to hard, and an emphasis on blurry atmospheric edges ultimately derived from the Venetian tradition of “colore” (color as the basis of art) versus the Florentine tradition of “disegno” (drawing or design as the basis of art).

William Sartain, Old Meadow, ca. 1890, Private Collection, NY

Charles Melville Dewey, Long Island Sunset, ca.1910, Private Collection, NY

Charles Melville Dewey’s Long Island Sunset, c. 1910 is a classic example of using soft-edged forms to create a sense of ambiguity and timelessness, in which half seen and hinted forms heighten our sense of vague wonder.

Leonard Ochtman, Early Winter, ca. 1900, Private Collection, NY

This sense of eerie displacement and the disquiet of half revealed forms finds an echo in the reviews of Charles de Kay, here in a New York Times review of a Leonard Ochtman exhibition in 1905, see Early Winter, c. 1900: “In “Moonrise” these is the mystery of a half light from the veiled moon; in this a haystack on the left of the swale is just visible and trees are seen in the distance to the right faintly silhouetted against the sky. The mystery of veiled moons is deep in “Night,” where the effect of silence is shown in paint.” (NYT, Thu, Feb 2, 1905, p 9)

J. Francis Murphy, Spring Mist, 1905, Private Collection, NY

J Francis Murphy’s, Spring Mist, 1905 demonstrates the power of suggestion and the half-seen, how an array of soft-edged forms in a landscape can be wonderfully highlighted and invigorated by just a few hard-edged lines of dark pigment, in this case, the barest of broken jottings to invoke the presence of tree saplings emerging from the mist.

Charles Warren Eaton, Twilit Sky, ca. 1910, Private Collection, NY

Twilit Sky, c 1910 by Charles Warren Eaton displays how such soft-edged forms, organized in a rectangular format, can be flattened to project a captivating two-dimensional world of floating untethered bio forms, avatars of what Rothko would later achieve with his ineffable multi-forms.

An impulse to nearly complete abstraction is inherent in the Tonalist style and prefigured magnificently by Arthur Bowen Davies late watercolors, Misted Hills, 1922, and Cloudscape, 1922. Notice that in Misted Hills Davies has crisply outlined in black a few of the low-lying clouds to offer context for the eye, and a contrast to the otherwise amorphous forms that predominate; whereas in Cloudscape there are almost no hard-edges whatsoever except at a few demarcation points of horizontal forms where they hazily interact.

Arthur Bowen Davies, Misted Hills, ca. 1922, Private Collection, NY

Arthur Bowen Davies, Cloudscape, ca. 1922, Private Collection, NY

William Gedney Bunce, Venice Shimmer, 1912, Private Collection, NY

William Gedney Bunce’s Venice Shimmer, 1912 dramatically illustrates the artist’s relentless movement to simplification and the dispensing with realistic hard-edged imagery of any kind, until his late lagoon pictures verge on imaginative mindscapes, forays into space and time and the untrammeled play of expressive color and light, providing only the merest hint of a horizon line and a few hazy architectonic forms for safe anchorage.

Charles Warren Eaton, Quarter Moon, ca. 1910, Private Collection, NY

Something that Charles Warren Eaton approximated in his late watercolors, like Quarter Moon, c. 1910, where the far reaches of the landscape create hypnotic patterns that read both as flat forms on the paper and recessional space fading into distance, here tethered by a quarter moon and the harder-edged boulders on the foreground hilltop.

Frederick Kost, Nocturne, Staten Island, ca. 1895, Private Collection, NY

A similar feeling for the mystery of night and moonlight is echoed in William Kost’s Nocturne, Staten Island of 1895, where the sea and sky enfold the hinted lights of shipping along the harbor quay. Kost deploys a magnificent array of free-flowing paint marks, merging and parting seamlessly to cast their spell upon the glittering moonlit waves.

9) An emphasis on the broad, graphic, ultimately abstract reading of major forms, producing an immediacy of emotional response—feeling—to paintings, especially at a distance: Underlying all the technical and stylistic innovations of the Tonalist movement was an embrace of abstraction, first as a formal compositional mode, Aesthetic Tonalism, and later as a way of dramatizing the emotional impact of an artwork, prompted less by a progressive mantra than by a craftsman’s logic to produce imagery that had immediate visceral impact.

Leonard Ochtman, Spirit of Fall, Private Collection, NY

Here is an excerpt of a review by Charles de Kay in the New York Times of a 1905 exhibition of works by Leonard Ochtman, see Spirit of Fall, which demonstrates how the most perceptive critic of his day reacted to Tonalism’s inherently abstract energies: “[Ochtman’s painting] is a fine big tonal landscape with tender sky and a balanced composition, wedges of woodland to right and left . . . [the work] makes one feel the movement of conversing fields of wheat and green pasture with the road in the valley told by rows of trees and by the moving hay cart, while in the central distance one foretells the turn of the valley by the lay of the land.”

Leonard Ochtman, Early Winter, ca. 1900, Private Collection, NY

Ochtman’s, Early Winter, 1900 is informed entirely by its geometric design, how the wave-like horizontals of hills and radiant sky centered on the setting sun appeal to both our imaginative embrace of the symbolic and love of pattern, not to mention our enjoyment of the craftsmanship that transforms the real into a graspable aesthetic experience.

Ben Foster, Cornwall Stream, ca. 1905, Private Collection, NY

Ben Foster’s Cornwall Stream, 1905 elicits an immediate response due to the bold landforms describing a receding stream bank flanked by lines of diagonally retreating trees, capped by a slab of hills beyond, where a radiating diadem of clouds spills from the vast sky. The large abstract landscape elements and how they rhythmically play off one another provide the essential aesthetic drama of the work.

Robert Swain Gifford, Naushoun, ca. 1890, Private Collection, N

Naushon, 1890 by Robert Swain Gifford. The work has an immediate visceral impact due to the simplicity of the bold arrangement of its major landscape elements: somber hued foreground perch, middle ground—where the zigzag of a river or bay glitters enticingly, to a hazy distant horizon: a grandiloquent cloud filled sky soaring aloft: a vast and almost visionary experience holding the viewer spellbound as if from mountain aerie. Only a small fisherman’s hut in the middle ground offers a narrative point of interest, overshadowed by the abstract hugeness of earth, sky, and water.

Emil Carlsen, White Pine, 1926, Private Collection, NY

White Pine, Emil Carlsen’s vigorous, modernist rendition on the essential vertical and horizontal forms of a glade of trees—a composition unusually narrow and then cropped to dramatize its dramatic impact—demonstrates the formal abstracting power gained by a severe and minimalist rendition of the quotidian.

Arthur Bowen Davies Blue Distance, ca. 1926 Private Collection, NY

The near complete abstraction of Blue Distance by Arthur B. Davies again shows how the galvanic drive for abstraction among the Tonalists resulted in works of increasing emotional power, and ultimately, the projection of deep feeling, the sine qua non of its finest practitioners.

10) Emphasis on the elegiac poetry of landscape (reflecting the trauma of the Civil War): If there is a predominant emotional charge underlying the Tonalist style: nostalgia, reverie, melancholy, joyous recollection in times of sweet repose, it probably reflects the deep trauma of the Civil War and the relentless changes affecting American society in the following decades from rapid industrialization and urban growth. Such feelings of loss, dislocation, nostalgic longing for a lost and more peaceful world are best expressed in a fundamentally non-narrative art through poetry, metaphor, and non-specific allusion. Thus Tonalism’s prime locus was landscape, especially depictions of the intimate near-at-home farmlands and rural places—often at dusk or dawn, that display the once-upon-a-time presence of human habitation: abandoned fields, tumbled fieldstone fences, old roads and second growth forests. The absence of figures in the Tonalist landscape is almost universal, while the remnants of human presence cheek-by-jowl with the wild is a ubiquitous iconology in Tonalist art. This elegiac quality, a kind of quietist soothing poetry was remarked on like a mantra in period texts, here by Charles de Kay in the New York Times review of a Leonard Ochtman exhibition (see Ochtman’s Spirit of Fall, Greenwich, Fall Meadow, and Spring Colors) at the MacBeth Gallery in 1898: “Tender sentiment for and sympathy with nature’s softer moods are the features of Mr. Ochtman’s work, and, whether he paints the flush of dawn, the dreamy noon hour of a still Summer day, the rosy tints of sunset, or the misty, weird atmosphere of a Summer moonlit night, he is in tune with that side of nature which only a poet artist can adequately portray.” (NYT, Sat, Feb 5, 1898, p 18)

Leonard Ochtman, Spirit of Fall, Private Collection, NY

Leonard Ochtman, Fall Meadow, ca. 1910, Private Collection, NY

Leonard Ochtman, Spring Colors, ca. 1905, Private Collection, NY

Leonard Ochtman, Greenwich, 1896, Private Collection, NY

Franklin De Haven, Lakeside, 1885, Private Collection, NY

Early works of Aesthetic Tonalism from the 1880s and 1890s were particularly suited to evoking such post-bellum feelings of poignant loss; and one suspects that these memory-soaked landscapes offered much consolation for collectors. Franklin De Haven’s lush Lakeside, 1885 provides a quiet circumscribed scene of contemplation, where the detailed foreground of lake-shore rocks anchors the gaze with a firm footing, while the calm surface–a shimmering whisper to to the watcher’s pensive moods, is, in turn, framed by a hazy distant tree line evocative of memory’s passing.

Charles Warren Eaton, Forest Edge, 1904, Private Collection, NY

Or the bannered boughs of Charles Warren Eaton’s, Forest Edge, 1904, which to period eyes might well have evoked tattered battle flags at half-mast, or nature’s immemorial vigil upon the horrific slaughter that took place on Pennsylvanian fields just thirty-five years before. Perhaps, too, in the timbered-over hills of Connecticut, evocations of a long-ago slaughter of a different kind . . . and the slow renewal of the forests, as year by year the white pine returned to the abandoned farmer’s fields.

Losses expressed in homesteads gone to riot and ruin, populated by second growth saplings and tumbled fieldstone walls, as in Ben Foster’s Autumn Road, c. 1915 or Charles Harold Davis’, Autumn, 1910. Such imagery speaks volumes to the hundreds of thousands who never returned home to take on the family farm, and others who moved on west for better prospects.

Ben Foster, Autumn Road, ca. 1915, Private Collection, NY

Charles Harold Davis Autumn, ca. 1910, Private Collection, NY

William Sartain. Nonquit, ca. 1900, Private Collection, NY

Even a shore scene like William Sartain’s Nonquit, 1910, touches on an unrequited melancholy in the barebones arrangements of interlocking land forms veiled in patterns of shadow and light: a timeless sounding of memory, of the subjective intermingling of time present and past in the incandescent moment.

Such fleeting Proustian visions, when memory is triggered by vague recollections of a time out of mind, casts a mesmerizing spell over the most ordinary events and places, such as the turning of a empty road in Frederick Kost’s, Summer Shadows, c. 1910, or his equally haunting Southfield Marshes, Staten Island, c. 1895 in which emptiness and solitude are invoked, and so abandoning the viewer to their own melancholy remembrance.

Frederick Kost. Summer Shadows, ca. 1910 Private Collection, NY

Frederick Kost, Southfield Marshes, Staten Island, ca. 1895 Private Collection, NY

Charles Melville Dewey, Sunset, 1910, Private Collection, NY

And in one of the very few Tonalist works that included a figure, Charles Melville Dewey’s, Sunset, c. 1900, we see an iconic image of a returning soldier to the old homestead (here in the guise of a farmer returning from his fields, hoe slung over his shoulder), gazing upon the glory of a sunset horizon, reminder of day’s end and labors done, and the quiet joys to be found in the enduring certainties of hearth and home: and hopes for a nation at peace.

11) The portrayal of a mystical organic relationship between perceiver and the perceived (the transcendentalist subjectivity espoused by Emerson and Thoreau).: Hand in hand with the elegiac poetry of Tonalism, a style that provides consolation in the face of unimaginable horror, is the fundamentally spiritual dimension of Tonalism that offered a bereft nation a new focus for religiosity in all it many turn-of-the-century guises. The writings of the transcendentalists, Emerson and Thoreau, became widely read and absorbed by the cultivated public precisely in the years that saw the emergence and flourishing of the Tonalist movement as it replaced the more bombastic literalism of the Hudson River School. Thus a more subjective, mystical, and organic spirituality invested in the values of home ground infused Tonalism with concrete yet diffuse imagery that mirrors the spiritual yearning of the individual, a meaning as ineffable as the essentially human experience of solitude is universal. A review of a 1893 exhibition of Charles Warren Eaton, see Forest Edge, Gloaming Pines, Quarter Moon, Twilit Sky, touches on the spiritual dynamic of Tonalism in explicitly religious terminology: “He has many moods, but most of them thoughtful and are faintly touched with that sadness without which there is no perfect beauty. He is fond of veiled sunshine, of twilight, of moonbeams and candle gleams of the autumn time when foliage turns to clouds of brown and when forest aisles become places of haunting mystery. He prefers that nature shall be subjective—and manifestation of the thought; and that the thought which it symbolizes be gentle and pure.” (The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, Sun, Mar 12, 1893, p. 4)

Charles Warren Eaton, Forest Edge, 1904, Private Collection, NY

Charles Warren Eaton, Gloaming Pines, ca. 1910, Private Collection, NY

Charles Warren Eaton, Quarter Moon, ca. 1910, Private Collection, NY

Charles Warren Eaton, Twilit Sky, ca. 1910, Private Collection, NY

Similar religious imagery is invoked in a 1916 review, in the third catastrophic year of WWI, by Charles de Kay in the New York Times, reviewing an exhibition of Charles Melville Dewey: “The earth hangs in that atmosphere of peace which strikes most poignantly upon the human heart accustomed to the warring of complex emotions. The large silhouette of the tree masses, the breadth of the nobly designed sky, the solidity of the earth, are elements of that sense of security in the working of eternal laws throughout the universe which the sight of wide horizons at still moments inspires. Against this background of austere peace enters the light with its delicate slow song of lyric joy . . . . “(NYT, Sun, April 16, 1916, p. 78)

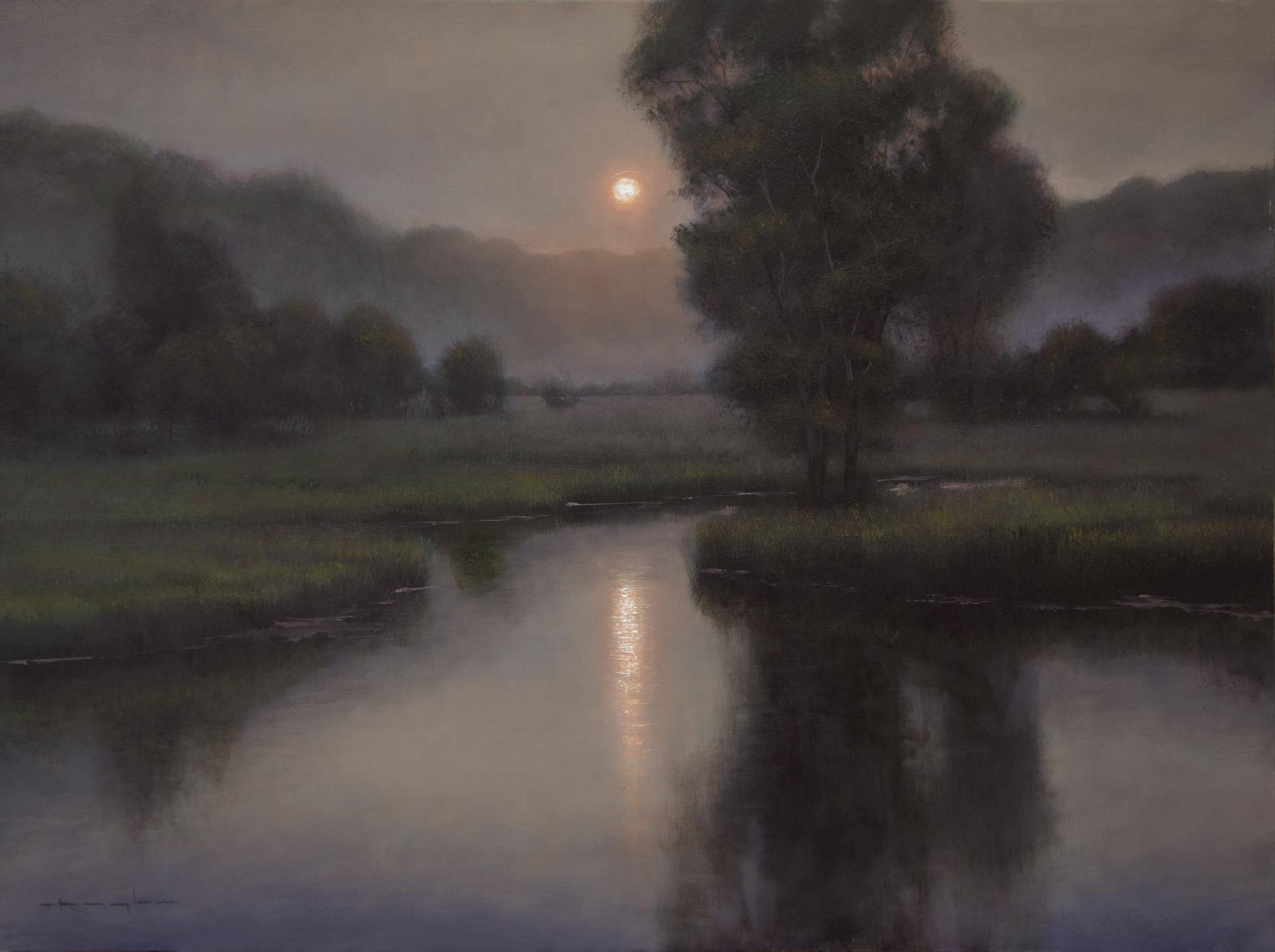

Charles Melville Dewey. Moonlit Reverie, ca. 1908, Private Collection, NY

Charles Melville Dewey, Return of the Hayboats, ca. 1892, Private Collection, NY

It is hard to conceive of another artistic movement beyond the great age of Medieval, Renaissance, and Baroque art so conceived in and so intimately responding to the evolving spiritual needs of a bereft people, dealing not only with loss but the many anxieties of rapid change in an age of rapid industrialization and social dislocation. This spiritual dimension, inherent in Tonalism, is reinforced and expressed by many of the style’s essential characteristics already enumerated: mysterious, ambiguous, suggestive, poetic, elegiac, quiet, solitary, timeless, memory-filled, symbolic, abstract, metamorphic, transcendent, subjective, expressive, intuiting the invisible or hidden, and employing colors muted, restful, and conducive to a meditative state of mind. Tonalism is an art for the contemplative spirit, a balm for body and soul.

Charles Harry Eaton, Sunset After a Strom, ca. 1890. Private Collection, NY

Ben Foster. Waning Day, ca. 1916, Private Collection, NY

12) A non-narrative synthetic art: an art about the feeling or mood evoked by the arrangement of landscape elements to project an emotion, rather than a realistic or representational depiction of a specific place: Finally, it cannot be stressed enough that the defining characteristic of Tonalist art, especially vis a vis French Impressionism and its American counterpart–if not competitors in Tonalism’s heyday, certainly an alternative technical style that Tonalists mostly rejected–is its strictly non-narrative stance and focus on describing the subjective feeling of landscape under subdued light. Tonalism is fundamentally a synthetic studio art, derived from field sketches and memory, but concentrating its picture-making energies on formal and abstract values that evoke emotion without recourse to an explicit story.

James Abbott McNeill Whistler, Nocturne: Blue and Gold—Old Battersea Bridge, 1872-1875, Smithsonian Freer and Sackler Galleries

Leonard Ochtman, A Silent Morning, 1909, Private Collection, NY

William Gedney Bunce, Sunset Variations, ca. 1900, Private Collection, NY

William Gedney Bunce, Beach Tides, ca. 1900, Private Collection, NY

Even an urban or town setting like Alexander Shilling’s, Winter Road, 1883, excludes the presence of pedestrians or hints of daily life; the same with Charles Fromuth’s Concarneau, 1893, where the often busy quayside serves solely as a prop for the artist’s exploration of muted color and the formal arrangement of trees and house-geometries in a snug harbor setting.

Alexander Shilling, Winter Road, 1883, Private Collection, NY

Charles Fromuth, Concarneau, 1893, Private Collection, NY

In this and so many other technical dimensions of the style, Tonalism was a sophisticated progressive force in the art scene of its day. By eschewing traditional narrative and the specifics of place, Tonalist artists intuited a subjective arrangement of natural symbols—untold stories at once exquisitely personal yet universal in import.

Henry Ward Ranger, The Woodland Scene, 1905, Private Collection, NY

Henry Ward Ranger, Ranger, Hillside Trees, 1905, Private Collection, NY

Life is not a thing of knowing only — nay, mere knowledge has properly no place at all save as it becomes the handmaiden of feeling and emotion.

Judge Learned Hand, 1893

Source: https://www.artsy.net/article/david-adams-cleveland-what-is-tonalism-12-essential-characteristics

David Adams Cleveland

David Adams Cleveland is a novelist and art historian. His latest novel, Time’s Betrayal, was acclaimed Best Historical Novel of 2017 by Reading the Past. In summer, 2014, his second novel, Love’s Attraction, became the top-selling hardback fiction for Barnes & Noble in New England. Fictionalcities.uk included Love’s Attraction on its list of top novels for 2013. His first novel, With a Gemlike Flame, drew wide praise for its evocation of Venice and the hunt for a lost masterpiece by Raphael. His most recent art history book, A History of American Tonalism, won the Silver Medal in Art History in the Book of the Year Awards, 2010; and Outstanding Academic Title 2011 from the American Library Association; it was the best selling American art history book in 2011 and 2012. David was a regular reviewer for Artnews, and has written for The Magazine Antiques, the American Art Review, and Dance Magazine. For almost a decade, he was the Arts Editor at Voice of America. He and his wife live in New York where he works as an art adviser with his son, Carter Cleveland, founder of Artsy.net, the new internet site making all the world’s art accessible to anyone with an internet connection. More about David and his publications can be found, here, on his author site.